In the main, stories of resistance have borne a masculine face of armed ghetto or partisan fighters. For too long the important role that women played in resistance has lacked recognition. The narrative of the female kashariyot (couriers) of the ghetto undergrounds in Nazi-occupied Europe is a remarkable story of courage. Kashariyot (derived from the Hebrew kesher or connection) was the name given to young female couriers because they provided a kesher for hundreds of thousands of Jews incarcerated in ghettos.

From the beginning of the German occupation of Poland in 1939, Jews were forced into ghettos to separate them from their Aryan neighbours and other Jewish communities. Ghetto walls prevented access to news, information, supplies or any assistance that might have helped them overcome their isolation. It was to remedy this that Jewish resistance groups conceived a daring plan — kashariyot. The members of this group, young females, could move beyond the walls of the ghettos to the rest of Poland, delivering news and aid. The girls also played an important role in fostering pride and resilience.

The kashariyot women shared a number of personal qualities. They were leaders of Jewish/Zionist youth movements (Dror, Akiva and Ha-Shomer ha-Zaír) or political parties (Jewish-Socialist Bund and the Communist Party). In physical appearance they were able to blend in with the general Polish population. (Blonde hair and blue eyes proved a distinct advantage in this regard). They were fluent in Polish without a Yiddish accent. They were young (most being aged between 15 and 25), strong, energetic, idealistic and fearless. Finally, they were female and could not be easily identified as Jewish, whereas Jewish men could easily be identified by circumcision.

The roles of the couriers changed as the ghetto underground resistance responded to shifts in German policy. When the ghettos were first established and most Jews were imprisoned behind walls, the focus of the underground organisations was to maintain contact with one another by exchanging news and illicit publications. Some groups participated in gathering information about German activities and smuggled in food to keep their families alive.

When the Germans began to murder Jews systematically in 1941 – the role of the kashariyot changed. They now spread news of impending death. As ‘human transmitters’, they saw, assessed and absorbed the plight of the ghettos, and were often the only witnesses to the obliteration of entire communities. They also faced the difficult task of convincing the Jewish leadership, the Judenräte, that Jews in the ghettos were marked for death. Their warnings alerted the youth within the ghettos, however, and the youth became leaders of the resistance, planning when and how to resist.

The kashariyot became responsible for acquiring arms, explosives and ammunition for the ghetto revolts and finding ways to smuggle them into the ghettos. They also smuggled money, messages, supplies and ammunition to groups of Jews planning to resist in camps and in the forests.

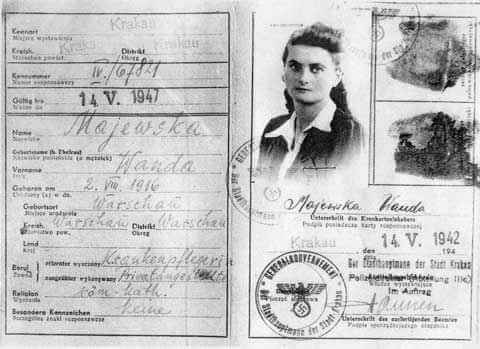

Once it became clear that the ghettos were being liquidated, the focus of the kashariyot turned to assisting children and adults to escape. They helped them to procure identity cards and find accommodation outside the ghetto walls. They also provided financial and emotional support for those in hiding. Overall, these young women played an indispensable role in the Jewish resistance.

Altogether, there were some 40-50 female couriers of the ghetto underground movements, of whom only a handful survived. Some of the better known Kashariyot include:

Tosia Altman, captured by the Germans and tortured to death, aged 25

Freya Beatus, committed suicide, aged 17

Liza Chapnik, lives in Israel, mid-90s

Marysia Feinmesser-Warman, lived in the Bronx, died in 2001

Havka Folman-Raban, lived in Jerusalem, died in 2014

Lonka Kozibronska, perished in Auschwitz, aged 26

Ala Margolis, lives in France, mid-90s

Vladka Meed, lived in Washington DC, died in 2013

Frumka Plotnika, killed while fighting in the uprising in Bendin, aged 29

Hancia Plotnika, captured and killed, aged 25 (Frumka’s sister)

Maryla Rozyska, partisan courier, died in the 1950s, aged in her mid-30s

Tamar Schneiderman, captured and sent to Treblinka, where she perished aged 25

Leah Silverstein, lives in Washington DC, mid-90s

Bronia Vinicka-Klibanski, lived in Jerusalem, died in 2011

Recommended Reading

Gelski, S. E. (1991). Survival Strategies of Jewish Polish Women 1918-1945: Towards Understanding the Role of the Female Couriers of the Warsaw and Bialystock Ghetto Underground Organisations. Unpublished honours thesis. Faculty of History, Deakin University.

Folman Raban, H. (2001). They Are Still With Me. Israel: Ghetto Fighters’ Museum.

Klibanski, B.(1998). In the Ghetto and in the Resistance: A Personal Narrative. In D. Ofer & L. Weitzman (Eds.), Women in the Holocaust (pp. 175-186). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lubetkin, Z. (1981). In the Days of Destruction and Revolt. Israel: Ghetto Fighters’ House

Meed, V. (1998). On Both Sides of the Wall. Israel: Ghetto Fighters’ House.

Szwayger, A, B. (1990). I Remember Nothing More: The Warsaw Children’s Hospital and the Jewish Resistance. New York: Pantheon Books.